Author: Takechika Hayashi (check out members); Translator: Katarina Woodman

In the great blooming, buzzing confusion of the outer world we pick out what our culture has already defined for us, and we tend to perceive that which we have picked out in the form stereotyped for us by our culture.

Walter Lippman

Questioning Standards

Let us suppose there are only two people in the world. “You” and “me.”

To tell us apart, we might make simple comparisons such as “I have long hair, and you have short hair,” or “You are talkative, and I am quiet.” In this way, the contrast between us can be drawn through direct, observable differences.

But now, let’s introduce a third person — “he.”

In this case, to describe him, you might list as many differences as possible among “you,” “me,” and “him,” comparing each characteristic in turn. Alternatively, a simpler way would be to establish the traits of “you” and “me” as a standard, and then describe how “he” differs from them. This latter approach becomes especially useful when a fourth or fifth person enters the picture. In fact, this is the one we rely on most often.

In other words, when we seek to understand ourselves or others, we do so by establishing a shared standard that can account for individual differences. Extending this logic to our understanding of the world, we might identify both external and internal criteria that are commonly shared among all of humankind (such as skin color, ways of thinking, religious beliefs, etc.), label the differences among them, and build our image of the world through contrasts between the self (or one’s in-group) and others (or out-groups).

Indeed, to understand the world may well mean to understand difference.

However, the “standards” we use are not necessarily universal. The standards by which you describe “him” may differ from those by how I describe “him.” For one, it may be skin color; for another, it may be religion.

In Japan, as an island nation, people who cross the sea are often categorized by the standard of whether they are “Japanese” or not, and thus are labeled “foreigners.”

This standard is deeply embedded in Japanese society and no longer merely a matter of individual labeling, but one that operates on the cultural and societal level.

Updating Standards

Now, let me share one particularly memorable conversation from our recent Kyoto University Academic Day 2025.

A Korean mother visited with her son, a first-year middle school student whose father is Japanese. She shared that when he was in elementary school, a friend once called him “Chōsenjin” (Korean). This deeply shocked him. Since then, he had been thinking about his identity. The friend, she explained, didn’t understand the historical implications of the term “Chōsenjin” and had used it as a geographic label referring to the Korean Peninsula.

Then, last year, a teacher told him something that changed his perspective: having two identities doesn’t make you half—it makes you double. From that moment, his confidence began to grow.

In this story, the friend, perhaps without realizing it, framed the child through a “regional origin” standard, defining him as “Korean” in opposition to “Japanese.” The child, in turn, internalized the standard of being “half,” and by accepting that label, the paradox of being both “Japanese” and “not Japanese” created conflict in his own identity. It took reframing the standard itself, from “half” to “double,” for his understanding of himself to change and allow him to embrace the entirety of his identity.

This story reveals a crucial insight: personal experiences can prompt us to reevaluate our standards, and by adjusting those standards, our understanding of ourselves and others can undergo a profound transformation.

In our research on world citizenship education, this is a meaningful discovery. A reminder of the importance of listening deeply to lived experiences and reconstructing our theories and hypotheses in light of them.

That day’s conversations also brought forward different perspectives. Stories of workplace tensions with foreign colleagues, classroom encounters with non-Japanese children, conflicts tied to religion or politics, and so on.

Though we might instinctively explain these situations through social labels, they offered something deeper: a chance to rethink the very standards we use when we look through the lens of lived experience.

Visitors’ Voices

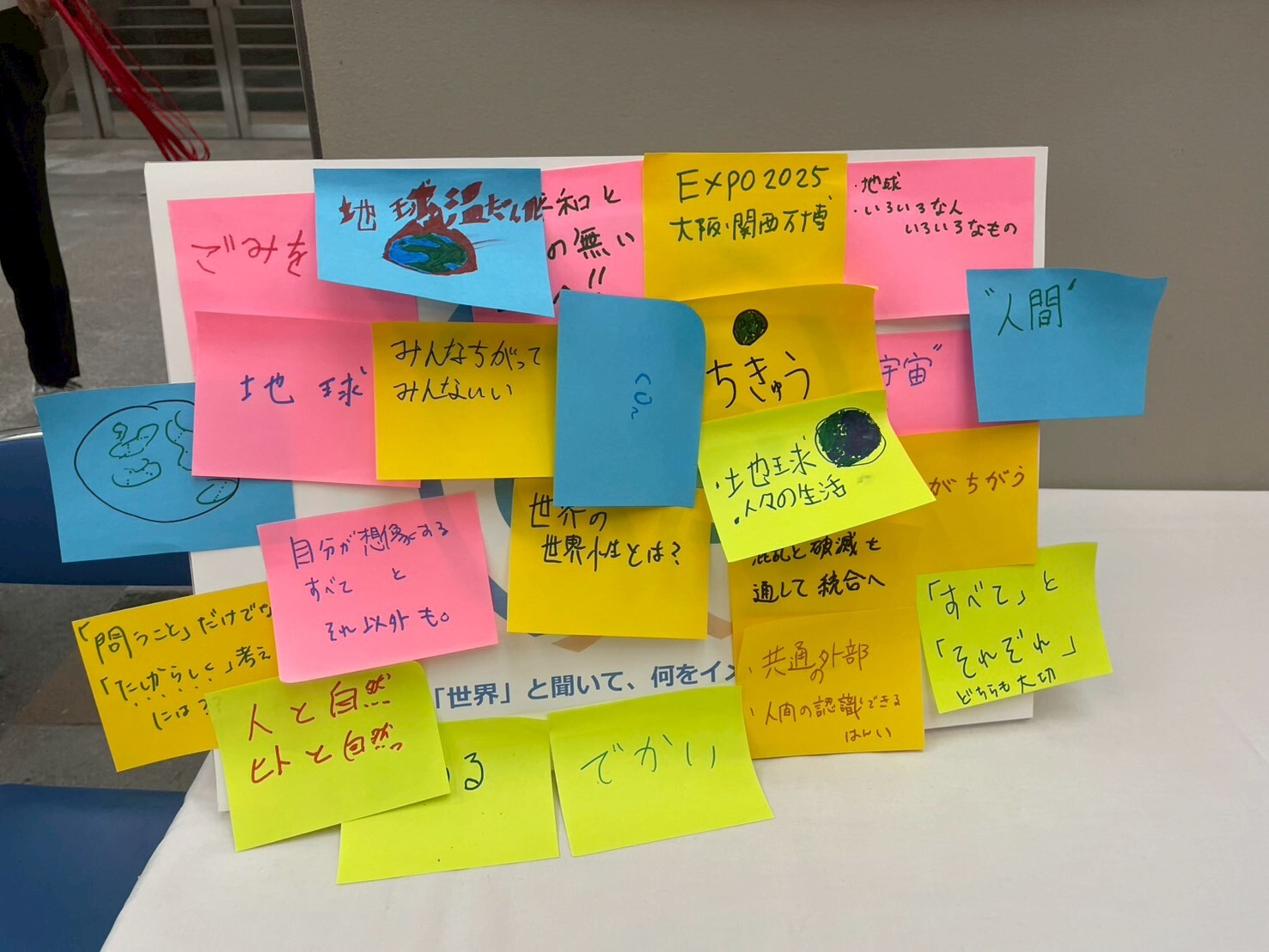

In light of this discussion, we also learned insights from the ways our visitors described their image of the “world.” Here we asked the question, “When you hear the word ‘world (世界),’ what do you imagine?

The interpretations of “world” varied widely. Some people envisioned tangible images like “the Earth” or “something big,” while many others described conceptual images such as “the world outside Japan.”

One man told us, “My world is Kansai. Anywhere I can’t reach by train is outside of my world.”

Among children, there were responses like “a place where the languages are different” and “where everyone is different and that’s okay,” defining the world as something distinct from their own experiences.

Next Blog

In the next post, we will explore the question, “What is our World Citizenship Education?” through interviews with the members of our project.